Un-Charted Waters

Keeping America's Water Safe After the Federal Data Pivot

A New Reality, A Shared Duty

Every one of us, regardless of our political or economic philosophy, shares a fundamental goal: safe, reliable water flowing from our taps. The debate we face today is not about the destination, but about the best path to get there. For fifty years, that path has been guided by a framework of centralized federal science, data collection, and regulatory oversight. A new framework is now being advanced, one that places its faith in decentralization, state-level control, and the power of market forces to drive innovation and efficiency.

My goal here is not to tell a reader who supports these changes that they are wrong, but to share my perspective in an effort to find consensus. And for those of us in the water industry, the time for this theoretical debate is over. A clear direction has been chosen, and this is our new reality. We don't have the luxury of second-guessing these decisions or relitigating them on social media. My family needs safe water today. And as a professional in this field, I am obligated to ensure your family is safe, too.

This creates a new, simpler definition of teamwork. If you are truly committed to keeping America's water safe, then you are on my team. We can and must figure out the details of how to succeed within this new reality, but our fundamental mission is the same. This article is my attempt to begin that process. It is an exploration of this new, decentralized approach, where we will steelman the case for its potential success before analyzing the challenges and risks as I see them. My hope is that by charting this new territory together, we can find a durable consensus on how to best protect our most vital resource.

The Federal Pivot: A Rapid, Multi-Front Reversal

This strategic pivot is not a distant proposal; it is a reality unfolding with remarkable speed. Documented in policy directives, budget allocations, and swift organizational restructuring, these actions represent a systematic and multi-pronged reversal of the federal government's long-standing role in the nation's scientific and data infrastructure.

The following list, while not comprehensive, details some of the specific changes that directly or indirectly affect the water industry. The full scope of these cuts extends into many other domains, and it is almost impossible to predict effects that will emerge from such a systemic shift.

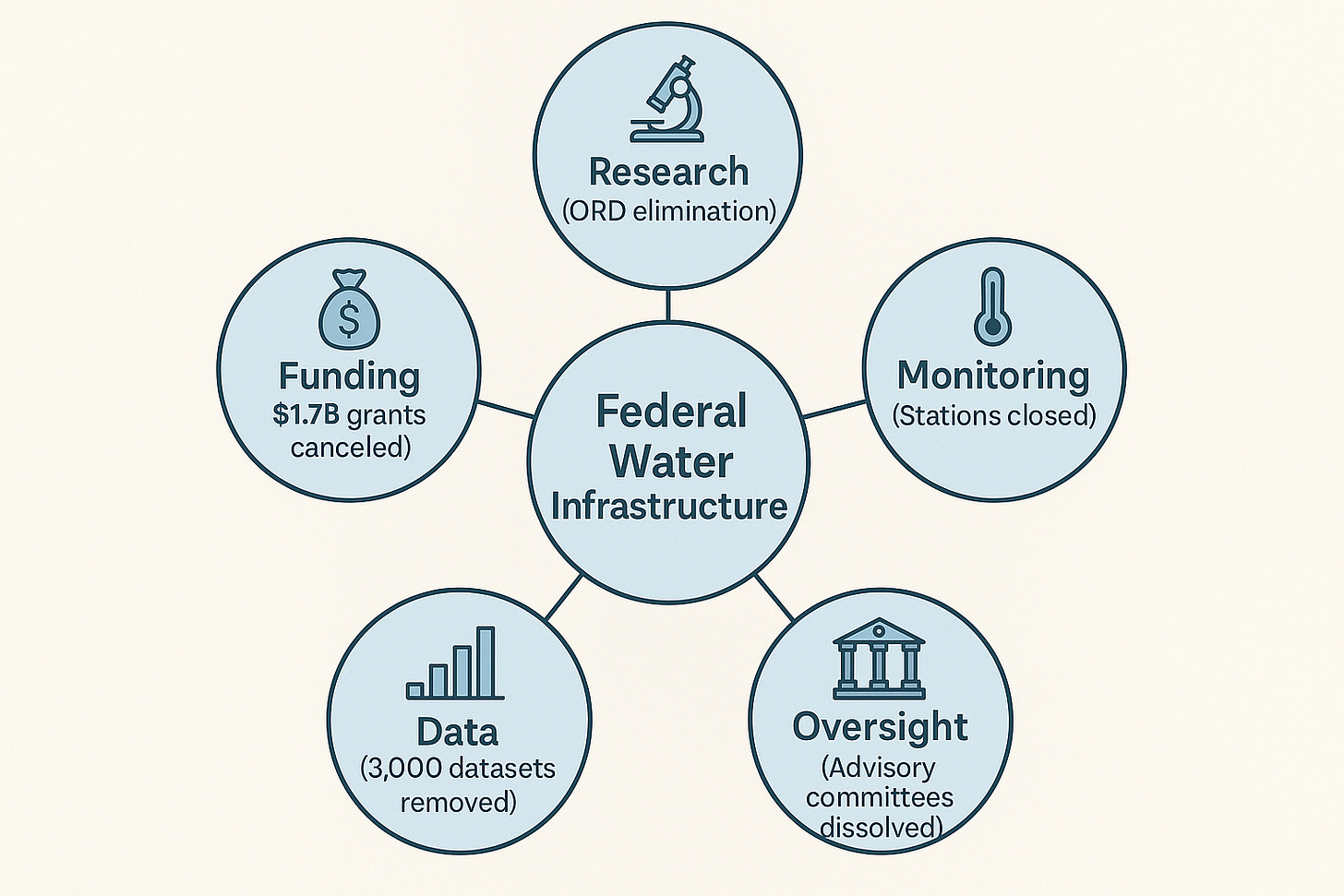

Environmental & EPA Actions

Elimination of Research Core: Complete elimination of the EPA's Office of Research and Development (ORD), the primary body analyzing toxic chemicals, water pollution, and environmental hazards.

Staff Reductions: Plans to cut the EPA by more than half, with a 23% staff reduction already underway and 672 scientists lost between 2016-2020.

Grant Cancellations: Cancellation of 400 grants totaling $1.7 billion aimed at improving air and water quality.

Water-Specific Impacts

Infrastructure Defunding: Near-complete elimination of federal water infrastructure funding, shifting an estimated $1.3 trillion upgrade burden to states and localities.

Deregulation of Waterways: Removal of Clean Water Act protections for one-fourth of US wetlands and one-fifth of US streams (690,000 stream miles), which provide over $250 billion in natural flood prevention.

PFAS Rule Rescission: Postponement and rescission of rules designed to limit "forever chemicals" (PFAS) in drinking water.

Monitoring Program Shutdowns: Elimination of water quality monitoring and watershed protection data programs previously managed by the eliminated EPA research office.

Climate & Atmospheric Science

NOAA Research Defunding: Zeroing out all funding for climate research at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), including the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR).

Lab & Facility Closures: Shutdown of climate laboratories, hurricane research facilities, and atmospheric monitoring stations nationwide, including the Mauna Loa Observatory.

Assessment Cancellation: Cancellation of the sixth edition of the National Climate Assessment (*site is taken down now) and dismissal of its hundreds of contributing scientists.

University Partnership Elimination: Elimination of all climate and weather cooperative institutes, cutting ties between NOAA and dozens of research universities.

Biology & Geological Science (USGS)

Assessment Cancellation: Cancellation of the National Nature Assessment, which details ecosystem and biodiversity impacts.

Staff Reductions: Loss of 150 staff scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

Monitoring Program Cuts: Elimination of water resource monitoring programs, reducing groundwater and surface water data collection critical for water management.

Data Access & Governance

Scientific Advisory Committee Elimination: Dissolution of at least one-third of all federal scientific advisory committees, with independent scientists on remaining committees often replaced by industry representatives.

Data Removal: Purging of over 3,000 taxpayer-funded datasets from federal websites, including data from the CDC and the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

Data Consolidation: Centralization of data control under the White House, eliminating traditional protections and requiring "unfettered access" to all unclassified agency records.

Taken together, this list demonstrates the systematic dismantling of the data infrastructure specifically relevant to the water industry, affecting everything from local water quality monitoring to long-term infrastructure planning.

The Immediate Consequences: The Landscape in 2025

The effects of this federal pivot are not speculative; they are tangible realities creating a new and challenging operational landscape for water professionals today. The long list of changes translates directly into immediate, cascading disruptions that are being felt across the country this year.

The Knowledge Vacuum Creates Regulatory Chaos The elimination of the EPA's Office of Research and Development (ORD) is having its most immediate impact on the nation's response to PFAS. Without the ORD's forward-looking research, utilities have lost their trusted, independent source for validating new treatment technologies and understanding health risks. This has created a "knowledge vacuum" where professionals are forced to navigate competing claims from technology vendors without a federal referee. Compounding this, the EPA's decision in May 2025 to withdraw proposed standards for four PFAS compounds while extending compliance deadlines for PFOA and PFOS has injected profound regulatory uncertainty. In response, states are not waiting. As of July 2025, at least 36 states are considering or have already adopted their own patchwork of PFAS regulations, creating a compliance nightmare for utilities and undermining the potential for a coherent national strategy.

The Infrastructure Funding Shock and Project Paralysis The proposed 90% cut to the State Revolving Funds (SRFs) in the White House budget, and even the less severe 25% cut proposed in the House, has sent an immediate shockwave through the municipal finance world. The uncertainty alone is a powerful force. Across the country, utilities are now forced to pause or indefinitely delay critical infrastructure projects planned for 2025. In California, for example, state officials have warned that crucial levee and dam safety projects are now in jeopardy. This forces utility managers into immediate, difficult conversations with their boards and ratepayers about significant rate hikes or the pursuit of privatization to cover funding gaps that were, until recently, expected to be filled by federal partnership.

Erosion of Trust and Compromised Oversight The visible dismantling of federal science is having an immediate effect on public trust. As federal capacity is reduced, and news of contamination crises continues to spread, public confidence in the safety of tap water is actively eroding. This is leading to an increased reliance on bottled water, a trend that disproportionately harms low-income communities and creates its own plastic waste crisis. Simultaneously, the replacement of independent scientists with industry representatives on key federal advisory committees means that the scientific review processes happening this year are operating under a different set of influences. For water professionals, this compromises a vital source of unbiased technical guidance and raises immediate questions about the scientific legitimacy of any new federal recommendations that are issued.

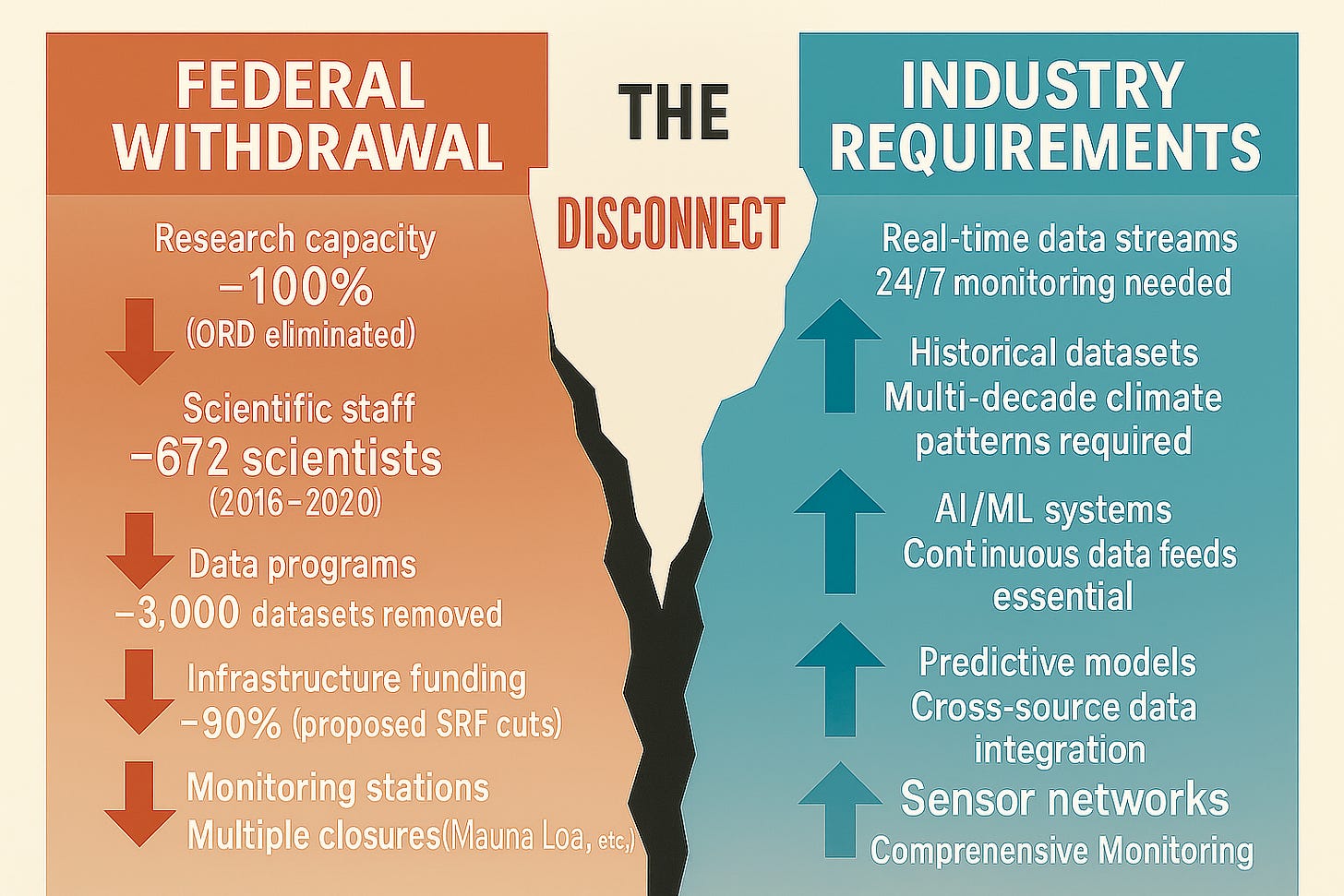

The Widening Chasm: The Collision of Policy and Technological Need The most profound disconnect in this new landscape is between the elimination of public data and the exponentially increasing data requirements of the modern water industry. The future of water treatment is being built on a foundation of data-intensive modeling, simulation, machine learning, and AI. These are not luxuries; they are becoming the core tools for ensuring safety and efficiency.

The Demand for Real-Time Data: Modern AI systems require continuous, real-time data streams—from flow rates and chemical concentrations in the plant to pressure differentials and fouling rates in membrane systems.

The Need for Historical Data: Predictive models are only as good as the data they are trained on. They require extensive historical datasets—on everything from multi-decade climate patterns to local water demand—to identify patterns and make accurate forecasts for equipment failure or contamination events.

The Requirement for Data Integration: These systems perform best when they can analyze vast amounts of data from multiple sources at once: sensor networks, satellite imagery, weather stations, and lab results.

The federal pivot directly conflicts with these needs. While the industry requires more 24/7 monitoring, more long-term datasets, and more multi-source data integration, the federal government is actively reducing its capacity in all three areas. This disconnect forces a difficult choice upon every water utility: either make massive new investments in their own private data collection and analysis systems or operate with reduced analytical capabilities, potentially compromising both efficiency and public health.

The Steelman Case: What Thoughtful Decentralization Would Look Like

To understand the full picture, it is essential to engage with the most compelling, good-faith argument for decentralization policies—not as they are being implemented, but as they could be implemented with genuine strategic intent. This is not a vision of neglect, but one of radical decentralization, predicated on a belief that market forces and local control can deliver superior results to a top-down federal bureaucracy.

What Thoughtful Implementation Would Look Like The core principle of this vision is that federal regulations are a one-size-fits-all burden that stifles innovation and imposes unnecessary costs. This viewpoint is championed by think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute, which have long argued for reducing the size and scope of federal agencies like the EPA. In its most sophisticated form, this philosophy of "cooperative federalism" would involve the federal government strategically stepping back to empower states while providing transitional support and maintaining coordination mechanisms. The ultimate goal would be to unleash market dynamism while ensuring no communities are left behind.

The Early Signals We'd Need to See For this vision to succeed, we would expect to see specific indicators of strategic implementation: federal agencies providing states with transition funding and technical assistance during the handoff, clear coordination mechanisms to prevent the "race to the bottom" problem, and robust investment in state-level scientific capacity. We would see market incentives carefully structured to reward innovation for public benefit, not just cost-cutting.

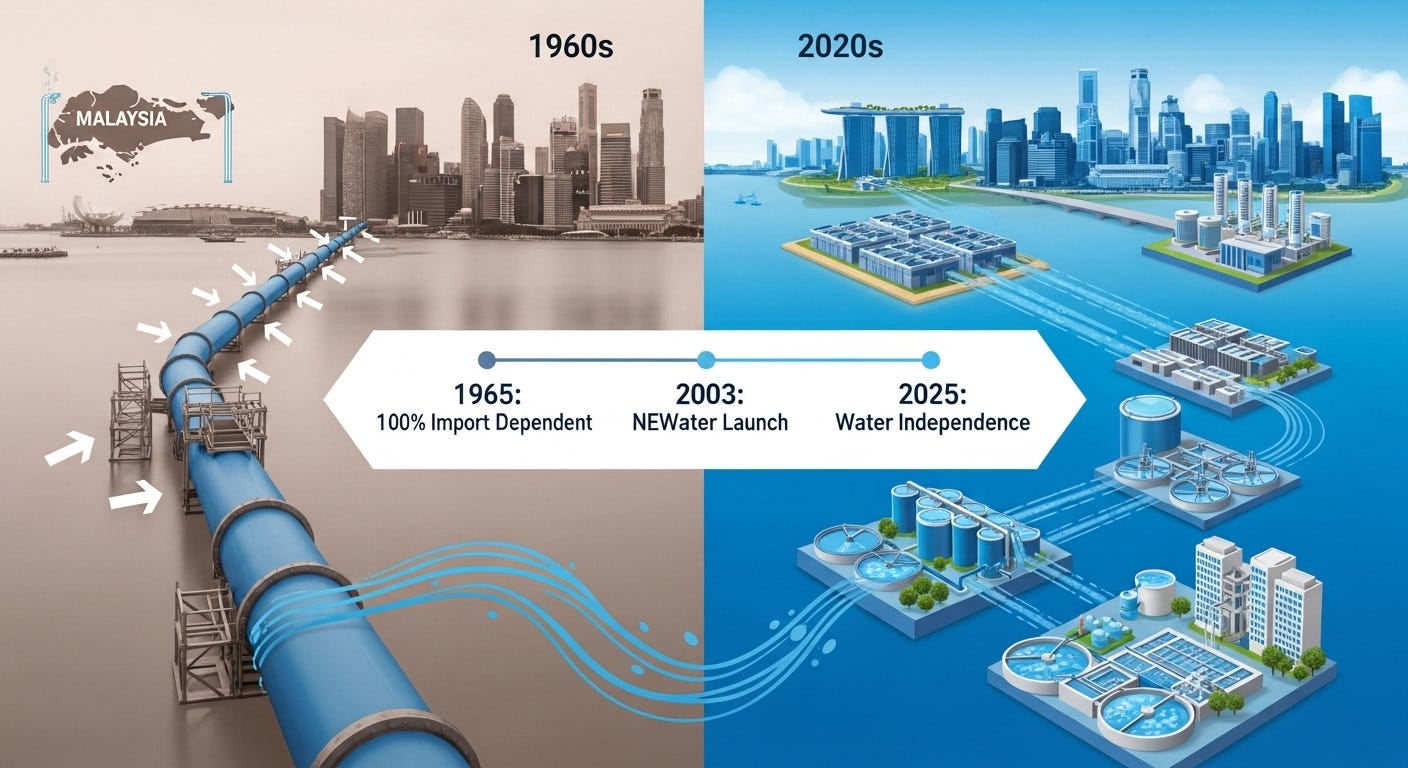

This model isn't purely theoretical. Singapore transformed from complete water dependence to technological leadership through exactly this kind of strategic decentralization. Faced with existential supply vulnerability in the 1960s-70s, Singapore's Public Utilities Board became an entrepreneurial innovator, developing advanced recycling ("NEWater") and desalination through aggressive public-private partnerships. Rather than waiting for regional coordination, they invested heavily in local capacity and market-driven solutions. The result? A world-leading water technology sector that now exports solutions globally, achieving water self-sufficiency decades ahead of schedule.

The Cascading Positive Effects (The Ideal Scenario) In this optimistic scenario, the federal withdrawal sets off a chain reaction of positive innovation:

First-Order Effect: Strategic Liberation. With the shackles of federal compliance costs removed, utilities can redirect vast amounts of capital toward their most pressing needs: replacing aging pipes and upgrading critical infrastructure. State environmental agencies, now empowered as the primary architects of policy, can design nimble, common-sense regulations that protect public health without crippling local economies.

Second-Order Effect: A Boom in "Water-Tech" Innovation. The knowledge vacuum creates a massive opportunity for the private sector. The PFAS crisis becomes the perfect catalyst. With no single federal standard, a fierce competition ensues among agile companies to develop cheaper, faster, and more effective solutions—from novel ion-exchange resins to advanced oxidation processes. Venture capital flows into "water-tech," and state regulators, working directly with utilities, can approve and deploy these new technologies in months, not the years it took for EPA validation.

Third-Order Effect: A Safer, More Affordable Future. This fierce market competition drives down the cost of PFAS treatment and other technologies. Utilities, operating with greater efficiency, can fund their infrastructure needs while keeping water rates stable. The U.S., having perfected this model of rapid, market-based innovation, becomes a global exporter of both water technology and this new, more effective regulatory framework.

The Fine Print: The Unspoken Conditions for Success

This optimistic vision, however, is not an automatic outcome. It is a fragile one that hinges on a series of challenging, perhaps unrealistic, conditions being met across the public and private sectors.

An Inconsistent Philosophy: Federal Preemption vs. States' Rights A critical inconsistency has emerged that challenges the core "states' rights" philosophy. While the administration champions decentralization, it has also shown a willingness to use federal power to compel states to rescind their own, more stringent regulations, particularly when they are seen as a barrier to economic activity. This creates a confusing and contradictory landscape where states are told to lead, but only in a direction that aligns with the federal government's economic agenda. This is not true decentralization; it is a selective application of federal power that undermines the very local control the framework purports to support.

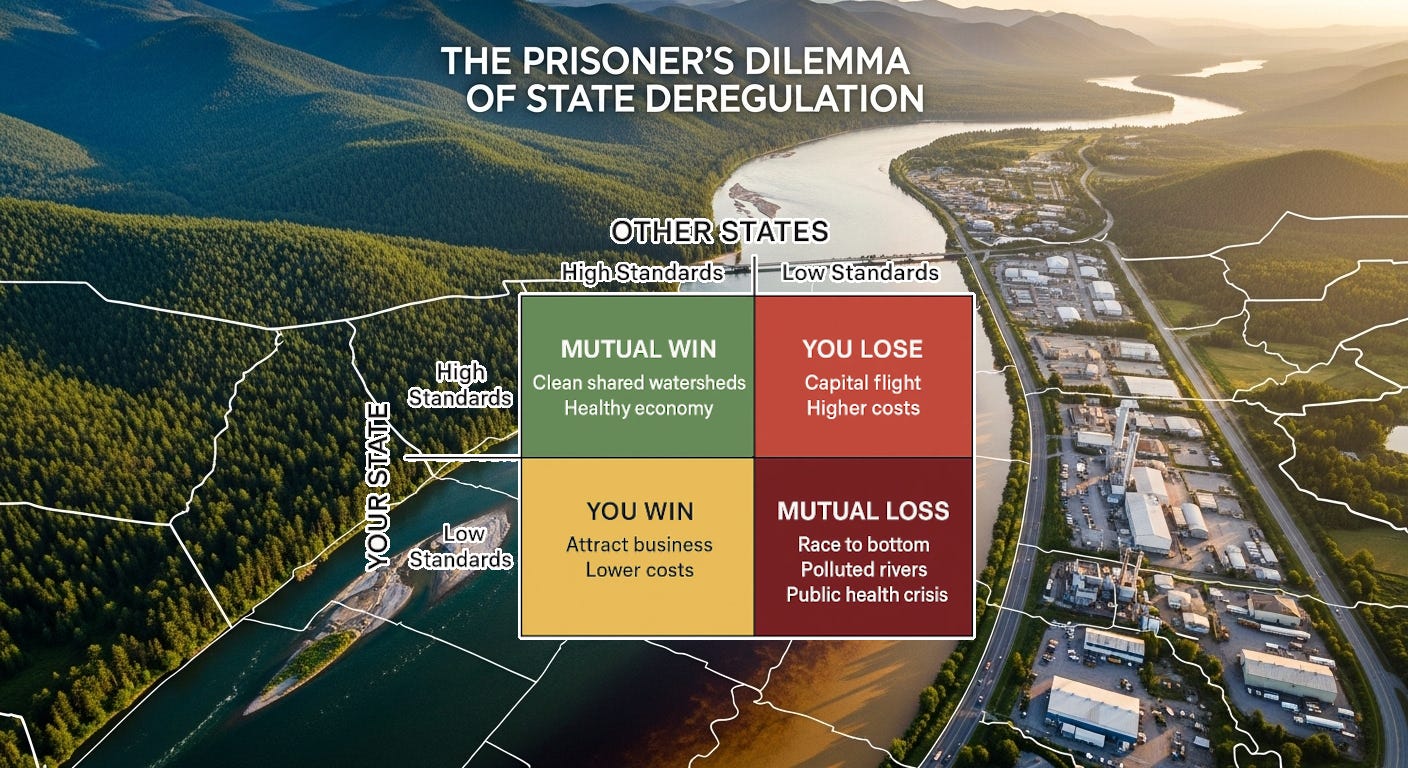

The "Hyper-Competent State" and the Prisoner's Dilemma of Deregulation The entire model depends on state environmental agencies transforming into world-class, independent scientific bodies, which would require massive new state-level investment. Without it, the more likely outcome is a destructive "race to the bottom," actively encouraged by federal rhetoric. When the EPA Administrator explicitly frames this shift as reducing "unfair burdens on the American people" and driving "down the cost of doing business," it signals to states that environmental deregulation is a valid economic development strategy. The revision of the "Waters of the United States" (WOTUS) rule to reduce "red tape" and cut permitting costs is a direct mechanism that enables this competition.

This creates a classic prisoner's dilemma. While it is in the collective best interest of all states to maintain high water quality standards for shared resources, it is in the short-term economic interest of any individual state to lower its standards to attract industry. This is accelerated by a dangerous feedback loop created by the elimination of federal data collection. Without federal tracking, states lack the comprehensive data to understand the true public health and environmental costs of their deregulation, interstate pollution effects go unmeasured, and the long-term consequences remain invisible until they become a crisis.

The "Enlightened" Private Sector and the Innovation Paradox The optimistic scenario assumes that private industry, freed from federal constraints, will innovate for the public good. This requires the sector to solve two fundamental problems: the trust gap and the innovation paradox.

The Trust Gap: Without the EPA to act as a referee, who validates that a new treatment technology is both safe and effective? This would require the emergence of independent, trusted third-party organizations—new NSF-style consortiums—to rigorously test and validate vendor claims. Without such a body, the market could devolve into a "pay-to-play" system where only the largest vendors can afford certification, or a chaotic landscape where utilities are paralyzed by the inability to verify competing claims.

The Innovation Paradox: While a lack of federal standards creates a market opportunity, it also creates market chaos. Without a clear regulatory target—like a federal Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL)—tech companies may be incentivized to develop cheaper, less effective solutions that meet a patchwork of weak state standards rather than investing in more robust, expensive R&D. Furthermore, a commitment to open-source data standards would be required to prevent a few dominant tech companies from creating proprietary, closed ecosystems that lock utilities into expensive, long-term contracts and stifle broader innovation.

The "Revolutionized" Public Utility and the Human Capital Crisis Finally, the optimistic scenario requires public water utilities themselves to undergo a profound cultural and operational transformation, shifting from a risk-averse, compliance-driven mindset to a proactive, entrepreneurial one. This is perhaps the steepest climb of all.

The Human Capital Crisis: The water industry is facing a "silver tsunami" of retirements, and it has not traditionally competed for talent against the tech and finance sectors. This transformation requires a new generation of leadership with skills in data science, technology assessment, venture capital-style risk analysis, and complex public-private partnership negotiation. Attracting and retaining this talent in a traditionally conservative public sector environment is a massive, unsolved challenge.

The Mandate for Radical Transparency: Without the political cover of federal mandates, every major investment—from a new PFAS treatment system to a smart meter rollout—must be "sold" to the public to secure the necessary political and financial buy-in for rate adjustments. This requires a level of radical transparency and sophisticated public communication about operations, water quality data, and financial health that is a new and demanding core competency for most utilities.

But what happens if these demanding conditions aren't met?

The Long-Term Fallout: A Forecast of the Negative Cascade

If the demanding conditions for success outlined here are not met, the immediate disruptions of 2025 will almost certainly evolve into deeper, more systemic, and longer-lasting crises. This analysis now shifts from a diagnosis of the present to a prognosis for the future, forecasting the long-term trajectory of these challenges as they ripple through the industry and society.

First-Order Effect: The Normalization of the Void The initial shock of the federal pivot—the loss of research, standards, funding, and data—becomes the new, degraded baseline. The "knowledge vacuum" is no longer a temporary crisis but a permanent operational reality, fundamentally altering the industry's ability to anticipate and respond to new threats.

Second-Order Effects: The Industry's Systemic Decay

Flying Blind into the Next Crisis: The "knowledge gap" becomes a permanent state of unpreparedness. With the ORD gone, the non-commercial, foundational science required to identify the next PFAS is simply not being done at a national level. Utilities are locked into a reactive posture, forever chasing the last crisis instead of preparing for the next one.

The Infrastructure Death Spiral: The "infrastructure deficit" accelerates into a death spiral for many small and mid-sized utilities. Crippling funding cuts force a cycle of deferred maintenance, leading to more frequent main breaks, boil water advisories, and catastrophic failures. This decay leads to credit downgrades from bond rating agencies, making it impossible to borrow money for even the most critical repairs and accelerating the push toward privatization.

The Chaos of Un-insurability: The "accountability void" creates a landscape of profound legal and financial risk. Without a clear federal standard of care, it becomes increasingly difficult for utilities to defend themselves in court against claims related to unregulated contaminants. Insurers, unable to accurately price risk in such a chaotic regulatory environment, may begin to deem public utilities "uninsurable," a move that could trigger financial collapse.

Third-Order Effects: The Fracturing of Society

A Two-Tiered Water System Becomes Entrenched: The geographic disparities in water safety solidify into a two-tiered system. Wealthier communities, able to fund advanced treatment through higher rates, will have access to safe water. Poorer, often rural, communities will be left with aging systems unable to cope with new contaminants, creating deep and lasting environmental justice crises with measurable public health consequences.

The U.S. Becomes a Follower, Not a Leader: As American R&D stalls, the U.S. will cede its leadership in the multi-billion-dollar global water technology market. Companies in Europe and Asia, backed by strong government research and clear standards, will dominate. American utilities will become customers of foreign technology, importing solutions they once helped to create.

The Collapse of Trust and the Rise of Conflict: The widespread public trust in tap water, a cornerstone of public health for a century, will collapse. This will trigger a boom in "citizen science" and direct-action environmental groups, leading to a wave of confrontational class-action lawsuits. On a larger scale, states at the downstream end of major, newly polluted rivers like the Mississippi will sue their upstream neighbors, leading to protracted and expensive "water wars" that escalate to the Supreme Court.

Conclusion: A Call to Build

We began this exploration by acknowledging two competing frameworks for achieving our shared goal of safe water. One, a half-century of centralized federal science. The other, a new vision of decentralized, market-driven innovation. After a sober analysis of the facts on the ground, the immediate consequences, and the high barriers to success for this new model, it is clear that the risks of a negative cascade are severe.

But to end there would be to miss the most important point. As we stated in the beginning, the theoretical debate is over. The federal pivot is our new reality. To simply lament this fact is a luxury we cannot afford. The critical question is not "what if," but "what now?"

While the theoretical framework of decentralization has merit, the current implementation shows few signs of the strategic thinking and transitional support required for success. This makes building alternative approaches not just wise, but urgent. For those who cling to the old model, waiting for Washington to restore the past, the future is perilous. But for those who recognize this moment for what it is—a forced opportunity to innovate, collaborate, and lead—the chance to build a smarter, more resilient, and truly self-reliant water future is at hand. The work of charting this new territory, of building a better system from the ground up, must begin now. It is no longer a choice, but a shared and urgent duty.

Thanks for sharing this writeup. What's your protocol for writing these out of curiosity?