Stevie Nicks Saves the Water Dept.

Understanding Organizational Path Dependency

Lindsey Buckingham sits at a desk in the Record Plant studio in Sausalito, the San Francisco bay shrouded in a late-night fog. It’s 1976. The words for a new song are in his head, but his typing on the rented typewriter is slow, clumsy. He hunts for the keys. What he doesn’t ponder, in his frustration, is why the typewriter is laid out this way, or where the dang ‘G’ key is.

Well, it was laid out that way to intentionally be hard to type on. Designed in the 1870s to prevent the mechanical arms of early typewriters from jamming, its layout is objectively inefficient for modern typing. It’s over 150 years later, and I’m currently using the same, stupid format to write this.

This invisible force, this ghost of a past solution, didn’t just haunt Lindsey’s typewriter. It haunted his band.

Consider Fleetwood Mac itself. During their 1977 masterpiece Rumours, they developed a unique working method perfectly suited to its context: turning their shared, immediate romantic breakups with each other into brutally honest, confessional songs. This "therapy through songwriting" was the optimal path for that specific crisis and led to legendary success.

However, the method became an ingrained workflow they defaulted to a decade later for their album Tango in the Night. By then, the context had changed; the members were older, the breakups were history, and their solo careers had created distance. The old path of turning conflict into art was no longer optimal; it became destructive, fueling old tensions and leading directly to Buckingham quitting the band at the peak of the album's success. The very process that first made them superstars ultimately fractured them because it was a relic of a past context, tragically misapplied to the present.

Rumours: The Invisible Chains of Your Organization

This dynamic isn't unique to rock bands. In every established institution—especially in a critical sector like water treatment—we are all guided by invisible chains, a phenomenon known as path dependency. Some paths, like Fleetwood Mac's creative process, become prisons. Others provide strength.

Think about your organization's meeting culture. Those weekly status meetings where everyone reads their reports out loud while half the room checks email? That's a chain that binds—a path that wastes time and kills engagement. But your emergency response protocols? The clear chain of command and communication that kicks in during a main break at 2 AM? That's a chain that connects—a path that saves lives and builds public trust.

Your organization has both types of paths. There are chains that bind you and chains that give you strength. The defining strategic challenge for a modern leader is learning to tell the difference.

Don't Stop (Thinking About Tomorrow)

Walk into any treatment plant built in the 1990s and you'll see the same proprietary SCADA systems running the show. Not because they're the best available today, but because they got there first and built a fortress around themselves.

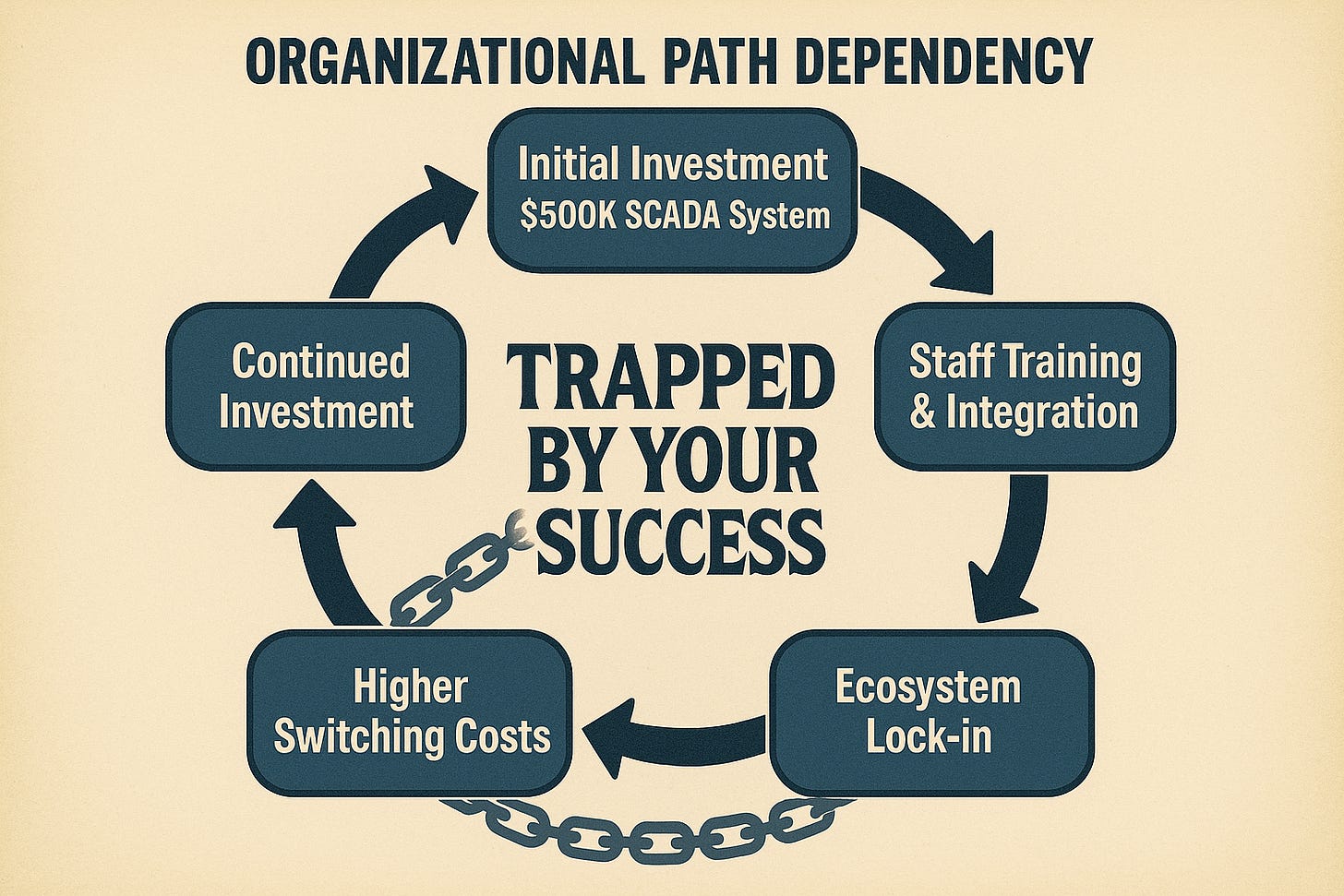

I can guarantee you've seen this. A utility drops half a million on a Wonderware system, then another $200K five years later for the analytics tool expansion. It works fine, so every subsequent expansion has to be compatible with that platform. Operators get trained on those specific screens and alarm structures. The maintenance contract locks you into that vendor's update cycle and pricing. Twenty years later, you're paying premium prices for software that looks like it was designed for Windows 95, because the true cost of switching isn't just buying new software—it's retraining your entire workforce, rebuilding every graphic display, and getting all your regulatory documentation revalidated.

This is path dependency in action: small early decisions creating massive long-term consequences through what economists call "increasing returns" or self-reinforcement. Each additional investment in the existing path makes switching more expensive, until you're essentially trapped by your own success.

But not every path dependency is a multi-million dollar SCADA investment. Sometimes the chains that bind us are much smaller—and much easier to break.

Go Your Own Way: The Case of the Phantom Filter Log

For years, the hand-written filter log was the bane of the operations team. It was a source of constant complaining and friction between shifts. If the day shift got busy, they might wash a filter and forget to fill out the log. That meant the night shift, ultimately responsible for the final reports, had to drop everything and search through SCADA trends—headloss, turbidity, backwash flow—just to piece together what happened hours earlier.

It was like this forever. A total waste of time.

Whenever I asked why we needed to manually copy data that was already perfectly stored in the SCADA historian, the answer was always the same: "Water Quality needs the log." It was treated as gospel. The assumption was that this physical piece of paper was a critical document for the quality department.

One day, I decided to go my own way. I walked over to the Water Quality department and asked the supervisor how they used our filter log. He looked at me, confused. They didn't even know we were still keeping it. It was a holdover from a decade ago, from a time before they fully trusted the SCADA data for some long-forgotten reason. The "need" was a phantom.

The resolution was beautiful in its simplicity. We stopped writing the log immediately. But we didn't lose the format. We created a new SCADA display page that mimicked the old log sheet, pulling the data automatically from the historian. Operators could still see the data at a glance in the format they were used to, but the chain that bound them was broken.

The Chain: A Diagnostic Framework for Chains that Bind vs. Chains that Connect

My experience with the phantom filter log shows how a once-logical path can calcify into a chain that binds. This isn't a conflict between old and new - it's about diagnosing what we're dealing with.

The story reveals the critical difference between the two types of paths:

Chains that Bind:

These are systems or processes whose maintenance and opportunity costs now far outweigh their original benefits. They resist integration with modern tools and become more fragile over time. Like a river that has carved a canyon so deep it is now stuck, unable to change course even as the world changes around it.

Key Indicator: The answer to the question, "If we were starting from scratch today, would we build it this way?" is a resounding "No."

Chains that Connect:

These are the values, principles, and commitments that link you to your purpose and the trust people place in you. They create stability while enabling innovation within clear boundaries. Like the chain that connects an anchor to a ship - it doesn't trap the vessel, it keeps it from drifting while still allowing purposeful movement.

Key Indicator: The path represents a core competency that consistently reinforces the trust people place in you.

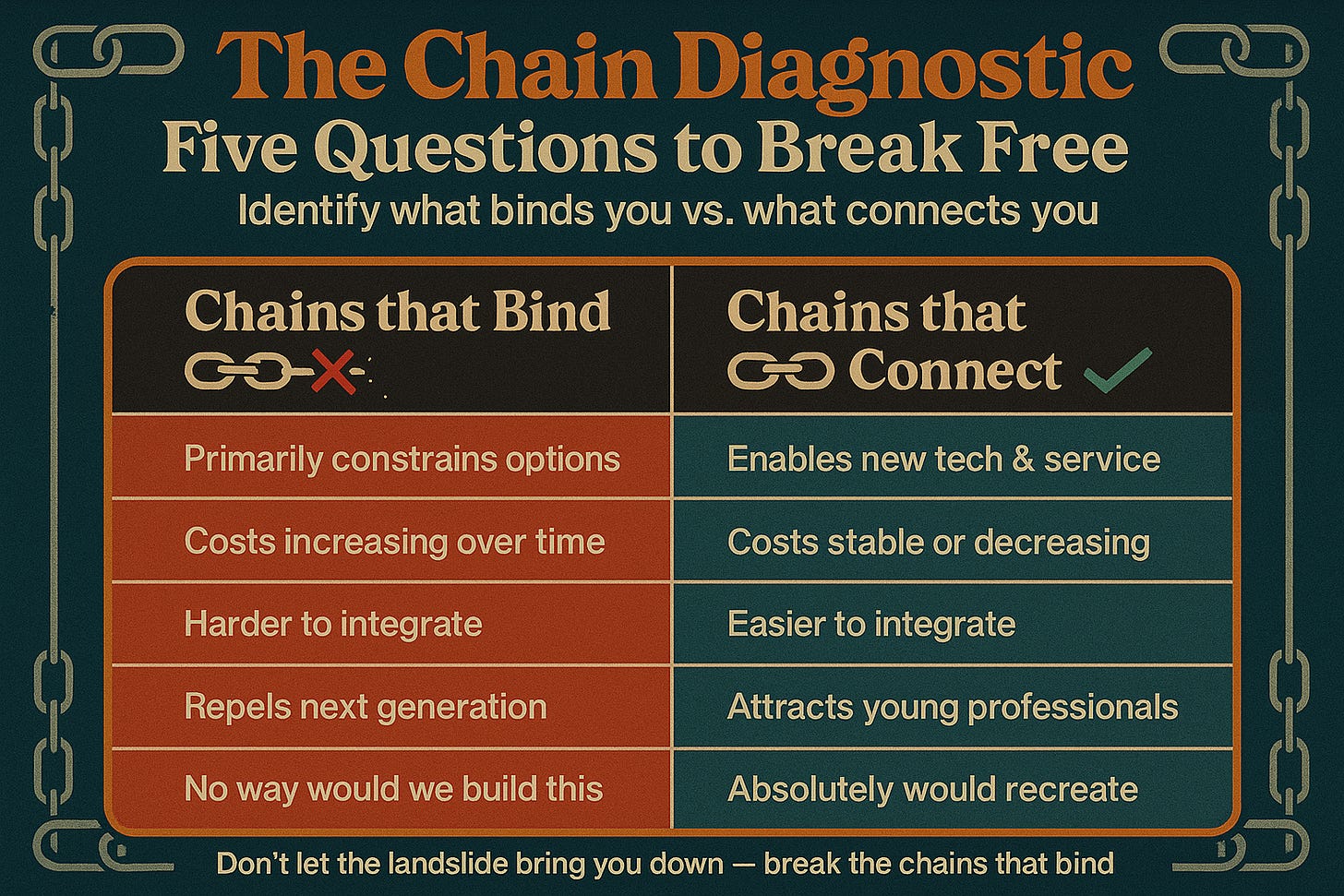

The Litmus Test: Five Questions to Diagnose Your Paths

Enabling vs. Constraining: Does this path enable us to adopt new technologies and improve service, or does it primarily constrain our options?

Cost Dynamics: Is the relative cost of maintaining this path (in money, time, and talent) increasing or decreasing over time?

Ecosystem Fit: Does this path make it easier or harder to integrate with new sensors, software, or partners?

Talent Magnet: Does expertise in this path attract or repel the next generation of water professionals?

The "Blank Slate" Test: If we were founded today to solve this exact problem, would we replicate this path on purpose?

Let's look at how this plays out across your operation:

Hard Infrastructure:

Chain that Binds: A monolithic concrete treatment basin designed for a single contaminant profile that no longer reflects the reality of your source water.

Chain that Connects: A modular, multi-barrier treatment train design that allows for the addition or reconfiguration of technologies like UV, AOP, or different membranes—a "platform" for treatment resilience.

Soft Infrastructure (Data & Processes):

Chain that Binds: The phantom filter log, requiring manual transcription of data that is already stored digitally.

Chain that Connects: Well-documented SOPs for critical processes like startup sequences or chemical dosing adjustments. They're not bureaucratic red tape; they're the institutional memory that keeps new operators from making dangerous mistakes.

Human Capital:

Chain that Binds: A promotion culture that primarily rewards tenure and mastery of an obsolete system, creating a "council of elders" who resist change.

Chain that Connects: Deep, institutional knowledge of your local watershed's unique hydrogeology or your distribution system's complex hydraulics. This is a scientific and operational "path" that forms the basis of all sound decision-making.

Ecosystems (Contracts & Reputation):

Chain that Binds: A sole-source contract for a proprietary chemical or filter cartridge that locks you into one vendor's pricing and innovation roadmap.

Chain that Connects: Your utility's brand reputation for impeccable water quality and reliability. This "path" of public trust guides every decision, creates customer loyalty, and secures funding.

Once you've mapped your chains, the intellectual work is done. Now, the real leadership work begins. Because every chain that binds is attached to someone's identity, someone's comfort zone, someone's career. Breaking them isn't a technical problem; it's a human one. It requires looking past the process and seeing the people—and that requires a different kind of reflection.

Landslide

One of the beautiful things about art is that its inspiration can find its way to places the creator never imagined. I love the song "Landslide." I would be enthralled to meet Ms. Stevie Nicks and find out if this article resonates with her. She says she wrote the song in 1973, feeling a sense of uncertainty and change in her life and career with Lindsey Buckingham. The song reflects her contemplation of whether to continue pursuing music with Buckingham or to return to school. And yet I listened to it and thought about my treatment plant.

That's the thing. Old ideas can be extremely valuable, but the current moment matters too. We can and should value where we came from and also update as we learn and grow.

Well, I've been 'fraid of changin'

'Cause I've built my life around you

But time makes you bolder

Even children get older

And I'm gettin' older, too

I'm gettin' older, too

Ah, take my love, take it down

Oh, climb a mountain and turn around

And if you see my reflection in the snow-covered hills

Well, the landslide will bring it down

And if you see my reflection in the snow-covered hills

Well, the landslide will bring it down

Oh, the landslide will bring it down

Now I turn it over to you. What is the "phantom filter log" in your organization? What is a chain you once thought connected you but now realize binds you?

Will you adapt, or will the landslide bring you down?