From Policy to Pipes

Priming the Pump for Change

Bridging the Gap from Policy to Pipes

Good ideas die in the gap between the boardroom and the pump station. The problem isn’t your people; it’s your system’s plumbing.

If you’ve spent any real time working in a water utility or any organization, you know the feeling. It’s the gap between the policy memo that promises a commitment to excellence and the frantic 3 a.m. phone call when a 12-inch main busts under the freeway. It’s a dead space in the organizational plumbing where good ideas from the field lose pressure before they can reach leadership, and well-intentioned procedures become hopelessly clogged in complexity before they ever reach the pipes.

Most of the time, this gap just creates friction and waste. But sometimes, it blows up into a full-blown catastrophe. Look at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s (LADWP) disastrous rollout of a new billing system in 2013. Leadership pushed the system live despite clear warnings from consultants and internal auditors that it wasn’t ready. The field staff who would actually use the system daily? They weren’t even consulted. The result was a complete disaster that hit customers hard. Families received bills for 40 times their usual amount. Thousands received no bills at all, overwhelming customer service and causing unpaid consumer debt to balloon by over $245 million.

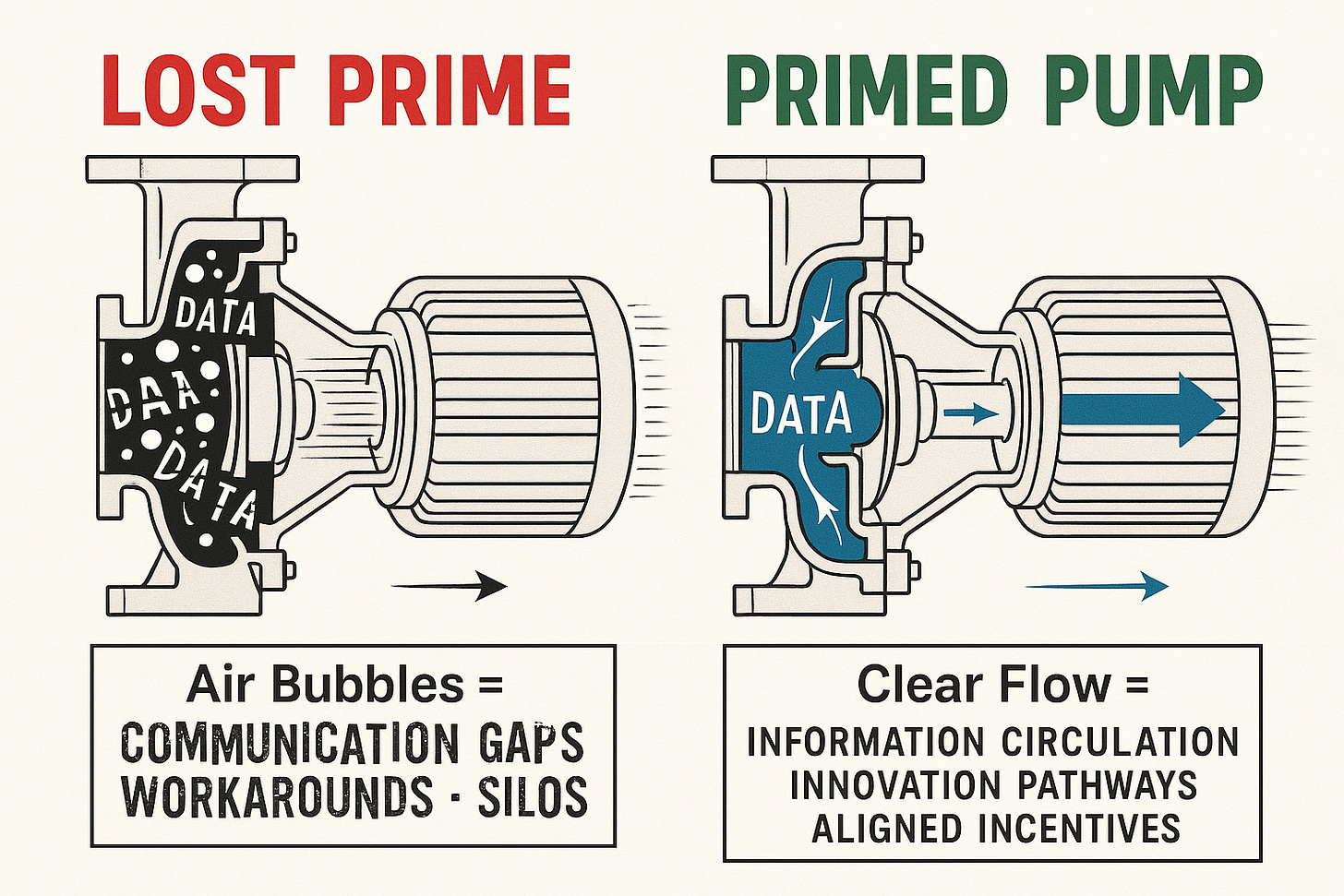

This wasn’t just a technology failure. It was a failure of communication: a chasm between the high-level decision to “go live” and the ground-level reality that the system was broken. The people who saw the problems coming couldn’t reach the people making the decisions. The easy answer is to blame people, budgets, or bureaucracy. But that’s a dead end. What if the real problem isn’t the people in the system, but the design of the system itself? What if we’re trying to force water through a pipe with a massive air bubble trapped in the pump? It’s like a pump that has lost its prime. The motor can scream at full speed, but the pump just spins, moving no water. The issue isn’t a lack of power or effort; it’s a mechanical failure. The solution isn’t to apply more pressure. It’s to stop, bleed the air from the line, and restore the conditions for natural flow.

The Case of the Expensive Workaround

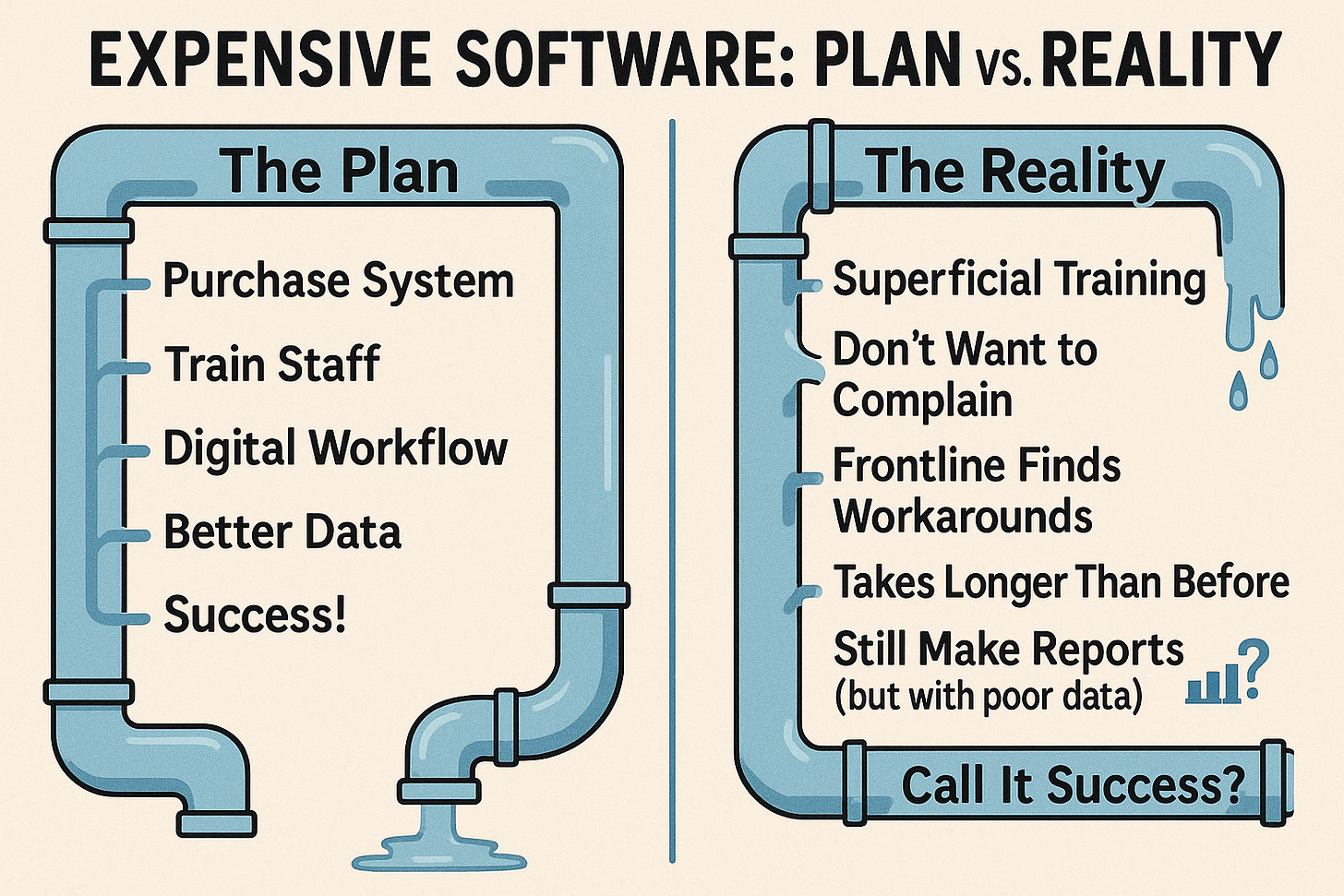

I've seen this pattern play out at a utility that invested heavily in IBM Maximo, one of the most comprehensive asset management systems on the market. It can track labor costs down to the minute, predict equipment failures based on maintenance history, and generate reports that would make any CFO weep with joy. In theory.

In practice, supervisors print out work orders from the expensive system so they can hand-write notes in the margins. Maintenance planners spend hours entering detailed asset data that field operators can never access when they actually need it. The utility gave journeymen iPads with the mobile version to log their hours in the field, thinking they’d finally bridge the digital divide. The interface was so clunky they ignored it entirely, until IT enabled their mobile access, which accidentally gave them desktop privileges. Now they use the desktop version because it’s easier, making the iPad rollout irrelevant.

This has been going on for years. The supervisors know the workarounds are inefficient, but they don’t want to tell their managers that the expensive system isn’t working, or sit through new training. The managers suspect something’s off, but they don’t ask because Maximo was a big investment and everyone wants it to be worth it. The longer this goes on, the harder it becomes to speak up.

The maintenance planners, the ones who actually manage the system, do present their case for fixing it. They need more staff to clean up the asset data. The trades need better computer skills. A coordinated training program would pay for itself in months. But management is unsure, and from what I can tell, it’s because they’ve never seen a well-functioning example. How do you invest in something when you can’t visualize what success looks like?

Meanwhile, each group has developed its own workaround silos. Supervisors keep handwritten logs. Operators use Excel to track what should be in Maximo. Planners duplicate data across systems. Everyone is working harder to avoid using the tool that’s supposed to make their work easier.

This isn’t a story about incompetent people or insufficient training. Everyone in this chain is intelligent and dedicated. This is about a system designed without understanding how the work actually flows between these groups and a gap between policy and pipes that can turn a major investment into an expensive source of daily frustration.

Mapping the Gap: Why Policy and Pipes Disconnect

The Maximo story isn’t just about one utility’s technology struggles. It’s a perfect illustration of a pattern that political scientist James Q. Wilson identified across all public organizations in his landmark work Bureaucracy. Wilson showed how different organizational levels naturally develop different priorities and measures of success, creating predictable communication breakdowns that have nothing to do with individual competence.

In water utilities, you can see Wilson’s three distinct levels at work, each operating with its own logic:

Executives respond to boards, regulators, and the media. Their success is measured by long-term budgets, regulatory compliance, and avoiding public crises. When they approved Maximo, they needed a solution that would demonstrate fiscal responsibility and provide the detailed reporting that regulators and board members demand. They need predictability and defensible decisions.

Managers get caught translating between executive demands for data-driven efficiency and the operational reality of how work actually gets done. They know the system isn’t working optimally, but they also know that admitting failure means questioning a major investment. They’re trapped between their bosses’ expectations and their workers’ frustrations, so they hope the problems will resolve themselves over time.

Operators deal with actual equipment, actual deadlines, and actual emergencies. Their success is measured by keeping water flowing safely, right now. When Maximo’s interface slows them down or provides incomplete information, they develop workarounds because their job performance depends on getting tasks completed, not on using the approved software perfectly

.

The Maximo dysfunction exists because of these natural tensions. Executives needed detailed reports they could show to boards and regulators. Managers needed to show implementation progress. Operators needed functional daily tools. But no one was responsible for ensuring these needs aligned, and the longer the dysfunction persisted, the harder it became for any single level to acknowledge the problem without implying criticism of the others.

Information simply wasn’t flowing. The operators’ workarounds never made it up to executives. The executives’ strategic vision never translated into operational reality. And the managers, caught in the middle, focused on managing the symptoms rather than addressing the root coordination failure.

Why Traditional Fixes Make Things Worse

How would most organizations try to “fix” the Maximo problem? With the “Push Harder” mentality. They would mandate more training, but without fixing the clunky interface. They’d implement stricter oversight, punishing supervisors for keeping handwritten logs or operators for using Excel. Or, most likely, they’d buy an expensive new module for the system, hoping technology will solve what is fundamentally a process and coordination problem.

This approach perfectly illustrates what former U.S. Deputy CTO Jennifer Pahlka calls “digitizing dysfunction.” Pahlka led efforts to modernize government technology and discovered that most failed IT projects shared a common flaw: they automated broken processes instead of fixing them first. The Maximo problem wasn’t a lack of features; the system was already comprehensive. It was a failure to design implementation around how the work actually flows between different groups.

A new training module wouldn’t address why the mobile interface is unusable in the field. Compliance enforcement wouldn’t solve the fundamental problem that operators can’t access the asset history they need when they need it. A new reporting dashboard wouldn’t fix the underlying issue that supervisors and planners are working with incomplete data.

Instead, these traditional fixes create a vicious cycle. Failed “solutions” generate more compliance pressure and oversight. Operators and supervisors become even more secretive about their workarounds, knowing that admitting problems might trigger another expensive fix that makes their daily work harder. Meanwhile, executives see continued investment without improved outcomes, leading them to conclude that the problem must be user resistance or insufficient training. The gap widens with each attempted solution.

The pattern is always the same: instead of addressing the system design that created the dysfunction, we add more pressure, more rules, and more technology. We try to force flow through a clogged system instead of clearing the blockage.

Priming the Pump: Creating Conditions for Natural Flow

We don’t solve the Maximo problem with more oversight or new tech modules. We solve it by “priming the pump,” creating the conditions for information to flow naturally. In a water system, priming removes air from the lines so that natural pressure can move fluid efficiently. In an organization, it means removing barriers so that information, innovation, and good decisions can circulate freely between Wilson’s three levels.

Here are four interventions to prime your utility’s pump:

Promote Information Circulation

The fix starts by getting operators, supervisors, planners, and managers in the same room to map out the actual workflow, not the theoretical one. In our case, this might reveal that supervisors print work orders because the system doesn’t show equipment location clearly enough for field use, or that operators use Excel because Maximo’s search function is too slow during emergencies.

Create systematic ways for this cross-level communication to happen. Hold monthly “field reality” briefings where front-line staff present directly to leadership with not just problems, but proposed solutions. Instead of asking “Why aren’t people using Maximo correctly?” ask “What would make Maximo actually useful for your daily work?” Start with operational needs and work backward to policy and technology configuration.

Build Innovation Pathways

Create safe-to-fail pilot programs where a small group can test workflow improvements. Maybe it’s simplifying the work order approval process, or creating custom dashboard views for different roles, or integrating Maximo with the tools people are already using effectively.

When a field innovation works (like operators discovering that desktop access is actually more efficient than the mobile version), have a formal process to evaluate and scale it rather than treating it as policy violation. Reward managers for surfacing both problems and solutions, not for maintaining the fiction that everything is working as designed.

Align Incentives

Stop measuring success by data entry compliance and start measuring by outcomes. A perfect record of entering labor hours into a system that provides no useful feedback is not success. It’s expensive theater. Instead, track whether maintenance decisions are getting better, whether asset failures are decreasing, whether work gets completed more efficiently.

Create recognition systems that value practical problem-solving over rigid procedure-following. Celebrate the planner who figures out how to make asset history accessible to field crews, not just the supervisor who has the highest work order completion rate.

Embrace User-Centered Design

The iPad rollout failed because it didn’t consider how the work actually happens. Instead of pushing a clunky mobile interface that nobody wanted, co-design solutions with the journeymen who will use them daily. Maybe they need offline access during outages, or voice-to-text capability when their hands are dirty, or integration with the truck’s GPS system.

Always start technology projects by understanding what your people actually need to accomplish, then design systems that support that work. Don’t ask “How do we get people to use this feature?” Ask “What would make people’s work easier and more effective?

”

What Success Looks Like

When a system is properly primed, the frustration of the expensive workaround is replaced by the satisfaction of effective tools. We can stop talking in abstractions and paint a clear “after” picture that contrasts directly with the “before” we know so well.

Before, supervisors printed work orders and scribbled notes in the margins. Success is when a supervisor in the field pulls up a complete, accurate asset history on their phone and makes a critical decision in minutes, not hours.

Before, operators used Excel because the official system was clunky and useless. Success is when an operator suggests a tweak to the system’s interface, and a month later, that tweak is rolled out because an innovation pathway actually exists to turn field insights into system improvements.

Before, planners entered data for compliance that nobody used for decisions. Success is when that same data entry directly informs a predictive maintenance schedule that prevents a costly failure, and that win is celebrated across the organization.

This is when the multiplier effect kicks in. Well-primed systems become self-improving. When operators trust that their input will be heard, they share more insights. When managers can turn field feedback into resource allocation, they become better translators between levels. When executives make decisions based on operational reality, those decisions actually improve outcomes. Trust builds on trust. Innovation enables more innovation.

From Forcing to Flowing

The chronic gap between policy and pipes isn’t a people problem or a resource problem. It’s a system design problem. For too long, we’ve tried to fix it by forcing flow, pushing harder with more rules, more technology, and more oversight. We’ve treated symptoms instead of causes, adding pressure instead of removing blockages.

When we shift from forcing to priming, the expertise and dedication that already exist in our utilities can finally circulate freely. The talent is there. The knowledge is there. The commitment to public service is there. What’s missing are the conditions for that expertise to flow between Wilson’s three levels and actually improve things.

The result isn’t just better compliance metrics or marginally improved efficiency; it’s an organization that learns, adapts, and improves continuously. It’s a utility where half-million-dollar investments actually deliver their promised value because the implementation process was designed around how the work really happens.

Your Turn

What is the “expensive workaround” in your organization? What system is everyone working around instead of working with? What phantom process continues because nobody wants to admit it’s not working?

The answer isn’t more training, stricter enforcement, or another software module. It’s priming the pump, creating conditions where the solutions your people already know can finally flow from the field to the policy level and back again.