Charting the Course

Four Strategic Questions Every Water Utility Must Answer

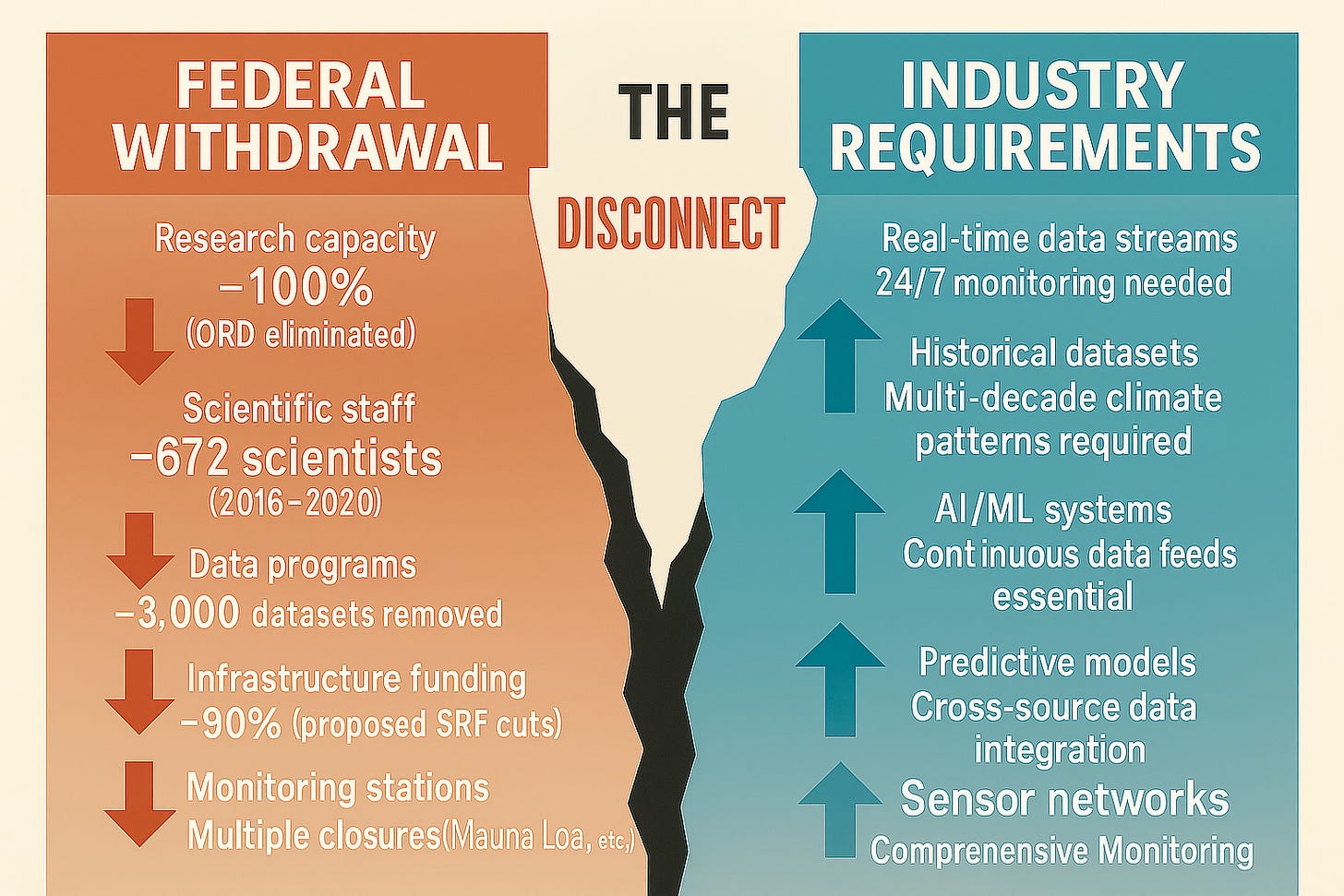

We began our last exploration by acknowledging two competing frameworks for achieving our shared goal of safe water. One, a half-century of centralized federal science. The other, a new vision of decentralized, market-driven innovation. After an honest look at what's actually happening, it is clear that the risks of a domino effect are severe.

But to end there would be to miss the most important point. The theoretical debate is over. The federal pivot is our new reality. To simply lament this fact is a luxury we cannot afford. The critical question is not "what if," but "what now?"

For those waiting for Washington to bring back the old system, the future looks grim. But for those who recognize this moment for what it is—a forced opportunity to innovate, collaborate, and lead—the chance to build a smarter, more resilient, and truly self-reliant water future is at hand. The work of charting this new territory, of building a better system from the ground up, must begin now. It is no longer a choice, but a shared and urgent duty.

The Four Questions Defining Our Future

The pioneers succeeding in this new landscape aren't just using better tools; they're thinking fundamentally differently about their role. The federal retreat has forced four fundamental questions on our industry that every utility is wrestling with, whether they realize it or not. How you answer these questions will determine whether you thrive in the post-federal future or get left behind.

Question 1: Who sets the standards when Washington steps back? For half a century, the answer was simple: the EPA conducted the research, set the standard, and our job was to comply. This created a culture of deference where local action waited for federal guidance. But when federal guidance disappears or becomes unreliable, leadership defaults to those with the capacity to act. The utilities adapting fastest have stopped asking "What does EPA want?" and started asking "What standard should we set for our region?" In short, are we building to a federal minimum or to our own community's needs?

Question 2: Is your data a competitive advantage or a compliance burden? Historically, operational data was something to be reported for compliance or protected as proprietary information. But the smartest utilities are discovering that shared intelligence creates analytical power no single utility could afford alone. This forces a fundamental choice: Do you treat data as a private liability to be protected, or as a shared strategic asset that grows in value when combined with peer data? Put simply, is data something you have to report or something you can put to work?

Question 3: When do you choose algorithms over concrete? The default answer to infrastructure problems has always been construction: bigger pipes, wholesale replacement, new facilities. But the math is changing. A network of sensors and predictive algorithms might achieve 80% of the outcome for 20% of the cost. The question isn't whether you'll ever need that bigger pipe—sometimes you absolutely will. The question is whether you evaluate technology as a substitute or complement before defaulting to construction. In short, should we dig a bigger trench or teach the pipes to talk?

Question 4: Is your finance team managing budgets or creating capital strategies? The traditional utility CFO managed budgets and passively administered grants. The infrastructure funding shock has made that approach obsolete. The utilities thriving today have finance teams that think like investment strategists. The question isn't "How do we get our share of shrinking grants?" but "How do we become strategic financiers who can access capital markets directly?" Put simply, is your CFO a scorekeeper or a dealmaker?

The Early Signals of a New Era

These questions aren't academic. I've been tracking examples across the industry, and the early signals of this transformation are clear. We're seeing states like California develop their own scientific capacity on PFAS that rivals federal expertise. We're seeing data collaboratives from the Carolinas to the West Coast turn shared data into predictive models that save millions. We're seeing cities like South Bend choose algorithms over concrete, and finance teams like Hampton Roads' become smart financial strategists.

These aren't isolated anecdotes; they are the templates for the future. Over the coming months, I'll be investigating each of these shifts in depth, sharing case studies and practical lessons from the utilities on the front lines. But before we can learn from these pioneers, we need to understand where we currently stand.

An Honest Assessment: Where Does Your Utility Stand?

Here's a question I've asked myself: If a board member asked you to justify why we chose a $12 million construction project over a $2 million sensor network, would I have a data-driven answer? The uncomfortable truth is that most of us are making infrastructure decisions without seriously considering the alternatives that new technology makes possible. South Bend faced exactly this choice—$700 million in tunnels and storage versus $40 million in sensors and algorithms. They chose the algorithms and saved ratepayers hundreds of millions. How many of us would have made the same choice?

Before you can chart a course forward, you need to know where you are now. These aren't gotcha questions. They're diagnostic tools to help you understand which of these four shifts represents your biggest opportunity—and your biggest risk.

On Regional Self-Reliance: When was the last time your utility co-funded actual research with a peer agency? When you attend state regulatory meetings, is your role primarily to listen and comply, or do you come prepared with data that influences policy?

On Data Collaboration: Can you name three peer utilities with whom you have a trusted enough relationship to share sensitive operational data? If a data scientist asked for five years of operational data in a standard format, could you produce it in hours, or would it take weeks?

On Intelligence-Driven Solutions: In your last Capital Improvement Plan, did you formally evaluate a technology-based alternative for every major construction project? Do you present the option of "deploy sensors and algorithms first, then build only what's still necessary"?

On Sophisticated Capital Strategy: Does your CFO regularly present financing options beyond municipal bonds and state grants? Have you ever modeled the financial impact of securing a WIFIA loan or issuing an Environmental Impact Bond?

The Hard Truth: Why This Is the Hardest Job in Infrastructure

This playbook makes the path forward sound linear and rational. It's not.

The federal pivot didn't just eliminate funding and research—it eliminated the federal support system that allowed us to move slowly and avoid risk. For fifty years, we could defer difficult partnerships because federal coordination would handle it. We could avoid sophisticated financing because federal grants would bridge the gap.

That safety net is gone, but the industry culture it created remains. I look around my plant and see staff who built their careers on compliance and incremental change, now being asked to become regional leaders and technology pioneers.

The human capital crisis isn't just about retirements—it's about asking people to develop entirely new skill sets while keeping aging systems running. The equity crisis is even starker: the utilities that can't make this transition fast enough will be left behind. Small communities that relied on federal support won't have access to the regional collaboratives and sophisticated financing that larger utilities are building.

The 2025-2027 window is critical because it's our last chance to build these new capabilities before the gaps become permanent. We're not just upgrading infrastructure—we're rebuilding how the entire industry works without federal support, while maintaining public health standards that have never been higher.

This is the hardest job in infrastructure because we're managing a transformation that was forced on us, not chosen by us, with stakes that couldn't be higher.